- This event has passed.

According to one study, heat could cause more than 17 million additional deaths worldwide by 2100. Wikimedia commons, CC BY-SA

François Lévêque, Mines Paris

This year, already marked by the hottest July ever recorded on Earth, heat-related deaths will still far exceed the hundred thousand mark worldwide. In 2022 in Europe alone, the summer season had already claimed almost 60,000 victims on the continent, including 5,000 in France.

But let's try to erase our emotions and see things from a distance, as Voltaire would have said, from the balcony of Sirius. With height, but without lecturing. Sirius was called Canicula by the Romans, in reference to the little bitch of the hunting god Orion, whose star it is close to.

Let's face it, then, the rise in temperature due to greenhouse gas emissions also reduces cold-related mortality; we need to count deaths per tonne of CO2, more or less - but also include deaths in the social cost of carbon; and finally, the good news is that our mitigation and adaptation efforts will save human lives by the millions.

Heat-related deaths, but also cold-related deaths

The excess mortality caused by global warming has been evident for several decades. Half a percent of total global mortality is in fact attributable to the effect of climate change on high temperatures. That's one-third of all heat-related deaths.

But the relationship between rising temperatures and mortality is not a one-way street. Warming also reduces the number of very cold days and peaks, and therefore the mortality associated with them. This does not refer specifically to the fact that people die of cold from hypothermia. Just as heat-related mortality is not limited to deaths from hyperthermia. Lower or higher temperatures weaken constitutions and accentuate pathological disorders, ultimately reducing life expectancy.

Warming therefore leads to more deaths on the one hand, but fewer on the other. This second phenomenon, which complicates the counting of mortality from new temperatures, can be very significant. In Mexico, for example, it has been calculated that a day above 32°C results in half a thousand deaths, but a day below 12°C in ten times as many. This is because very few homes have heating.

For the future, however, there is no serious doubt that compensation is only partial.

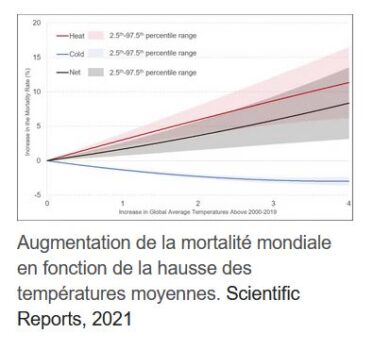

This is illustrated by the figure below, taken from an article published in Scientific Reports in 2021.

We should also mention a study that puts the additional deaths in 2100 linked to rising temperatures at 17.6 million - taking into account the under-mortality linked to cold. This figure is based on the assumption that there will be 8 billion people on the planet, and that the net increase in mortality will be 220 deaths per 100,000 inhabitants, the same ratio as today for cardiovascular deaths. This is considerable.

Increase in global mortality as a function of rising average temperatures. Scientific Report 2021

The under-mortality caused by the cold must be taken into account without shame or qualms, because it sheds a harsh light on the inequalities caused by global warming. It accentuates mortality disparities within the same state or union of states: between the populations of cold and hot regions of Mexico, India, the United States or Europe, for example. It reinforces inequalities between regions of the world: the United States and Europe are likely to experience slightly positive or even negative excess mortality due to rising temperatures by 2100.

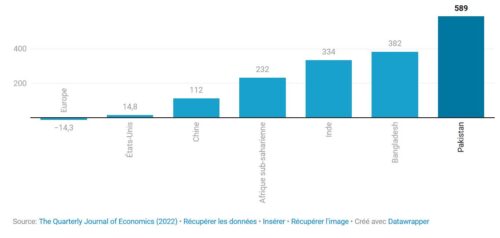

The above-mentioned average of 220 deaths per 100,000 inhabitants masks a very wide range, with ratios of +14.8/100,000 and -14.3/100,000 for the USA and Europe respectively.

Estimated excess mortality due to rising temperatures by 2100

Ratio per 100,000 inhabitants

According to a synthesis study published in 2022 under the aegis of the American Thoracic Society, cold-related mortality represents half of heat-related mortality in Europe, but only a quarter in the Middle East and North Africa region.

The starker inequalities once cold-related under-mortality is taken into account risk reinforcing egoism and making national and international political discussions on mitigation efforts even more difficult. But there's no point in burying our heads in the sand. Neither the expression nor the animal exist on Sirius.

A gauge you can use yourself

The development of work on temperature mortality provides a new vision and new results on the cost of carbon emissions. They make it possible to calculate the effects of global warming in terms of additional deaths per tonne of new emissions, and to integrate mortality into the determination of the social cost of carbon.

Explanation of this gibberish from a Sirian:

There are 0.000226 deaths associated with the emission of an additional tonne of carbon dioxide. Put another way and more precisely, reducing emissions of this gas by one million tonnes would save 226 human lives between 2020 and 2100.

More than 85,000 readers trust The Conversation newsletters to better understand the world's major issues. Subscribe today]

Let's make it even more telling: the emissions of four Americans during their lifetime correspond to one more death on the planet. This shocking figure and the previous ones are taken from an article by researcher Daniel Bressler, recently published in Nature Communications. They are based on the assumption of a temperature rise of +4.1°C in 2100 compared with the pre-industrial era, and an estimated cumulative excess heat-related mortality over this period of almost 100 million people.

This metric of additional mortality per tonne of carbon added or subtracted offers a simple way of assessing the effects of investment projects that emit new emissions or reduce them. You can even use it as a gauge when you're deciding whether to take the train or the plane! What's more, unlike the canonical metric of the social cost of carbon, i.e. the monetary cost to society of one tonne more or less, it avoids two constraints: that of choosing a discount rate and that of giving a dollar or euro value to a human life.

How much is a life worth?

You may remember a controversy between an American economist, William Nordhaus, and an English economist, Nicolas Stern, the latter of whom came up with a social cost of carbon incomparably higher than the former. The main reason for their divergence is a radically different position on the discount rate to be used, a parameter necessary to compare today's dollars or euros with tomorrow's dollars or euros. An acrobatic and perilous choice when tomorrow means 2100.

Assigning a monetary value to one human life less or more is an even more delicate and controversial choice. This is borne out by the countless economic studies that have been carried out over the last half-century on the statistical value of a life, and the fierce opposition this approach meets with from Earthlings who don't speak Sirian. Whether to take into account one less life or one less year of life is a first choice to be made, which I have discussed elsewhere.

This is decisive, as temperature-related mortality mainly concerns the elderly. A second crucial choice is whether to opt for a universal or an income-dependent value. In crude terms, is the death of an Indian worth less than that of an American? To discuss this choice would take us too far here.

Above all, it does not call into question the result I wish to emphasize: taking into account temperature-related mortality considerably alters the economic effects of global warming, with the loss of human life becoming the main item in the damage caused by global warming.

Take the example of William Nordhaus' 2016 climate-economy model. Mortality accounts for only a few percent of the damage. The deaths taken into account are essentially limited to those caused by the outdoor work of agricultural and construction workers. The social cost per tonne of carbon is 38 euros.

Using the same model, but adding all heat-related deaths, Daniel Bressler arrives at a social cost of carbon equal to $258 per tonne. This figure is based on a universal value of one year of life equal to four times the planet's average per capita consumption in 2020, or $48,000. Of course, the mortality cost of carbon is very sensitive to this value. At twice the value, the social cost of carbon becomes 177 dollars/t, while at twice the value, it becomes 414 dollars/t.

This result has been confirmed by other studies. A recent model incorporating a complete mortality damage module arrives at a social cost of carbon of $185/t, including $90/t for mortality alone.

Another article focusing solely on this item estimates it at $144/t, based on value-of-life assumptions and discount rates comparable to those used in Daniel Bressler's work. The authors also carry out multiple sensitivity analyses of the social cost of carbon mortality to these two variables. For example, the 144 euros/t must be divided by a factor of about 3 when moving from a 2% to a 3% discount rate, or when moving from the value of a universal life to the value of a life that varies according to countries' per capita income. In terms of years of life, however, the value is halved.

The future social cost of carbon under discussion today in the United States should take full account of the loss of human life. This is an important decision, as this data is used to evaluate public investment decisions. It is proposed by the Environment Agency and various experts that it should rise from today's $51/t to $185/t. Generally speaking, incorporating mortality into the social cost of carbon by significantly increasing it justifies much more far-reaching reduction actions. It makes them beneficial to the people of the world.

The great unknown of mitigation

The figures for temperature-related mortality over the next century mentioned so far are based on a pessimistic view of the future. They correspond to the scenario of continued greenhouse gas emissions at current rates - the so-called RCP 8.5 scenario of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC).

Reducing these emissions to allow temperatures to rise less would considerably limit the damage caused by mortality. Let's take the ratio of 220 deaths per 100,000 inhabitants in 2100. With emissions stabilized at a low level (the so-called RCP 4.5 scenario), the ratio falls to 40 deaths, i.e. more than five times less! If we take the aforementioned mortality cost of a tonne of carbon of 0.000226 , the effect is less considerable but still impressive: a temperature rise of 2.4°C instead of 4.1°C divides it by more than two.

Death in excess of the emissions of an average citizen of the world during his lifetime

![]() Scenario +4.1 degrees

Scenario +4.1 degrees ![]() Scenario + 2,4 degrees

Scenario + 2,4 degrees

Source: Nature communications (2021)Retrieve dataInsertRecover imageCreated with Datawrapper

The mitigation efforts we make will therefore save human lives in very large numbers. This positive consequence of the transition is not emphasized enough. Seen from Sirius, it offers a simple motivation and justification for Earthlings to make major decarbonization efforts.

The impossible adaptation equation

Whatever future temperatures are considered, mortality projections do not take into account another powerful lever for reducing the number of deaths: people's and society's ability to adapt to heat. Here again, the effects can be considerable.

They are, however, difficult to quantify globally. To my knowledge, only one study has attempted to do so. It found a 15% reduction in the risk of death. However, this result is based on a very restrictive set of assumptions, in particular the absence of public adaptation policies. Yet these play a key role. If only through the introduction of heatwave alerts and the dissemination of messages on the rules of conduct to adopt in order to protect oneself. In addition, numerous public investments have been made, particularly in cities, to combat heat islands.

Summer 2022 was the second hottest year on record in France - almost as hot as 2003. And yet, there were five times fewer excess deaths.

This gap suggests that society has made progress in adapting to repeated heat waves. This finding is confirmed by a model developed by epidemiologists and meteorologists. Applied to the 2006 heatwave in France, it shows that, without adaptation, it would have resulted in three times as many deaths.

In addition to public action, the progress observed can also be explained by the spread of air conditioning. We are all familiar with the deleterious effects of air conditioning, through its contribution to global warming via fossil fuel consumption, refrigerant gas leakage and, locally, its own hot air emissions. Less talked about are its consequent effects on reducing mortality.

An American study has shown that the spread of air conditioning in the USA between 1960 and 2004 prevented almost a million premature deaths. On the other hand, the reduced use of air conditioners in Japan, due to rising electricity prices and energy-saving campaigns following the Fukushima Daichi nuclear accident, led to almost 10,000 excess deaths.

Migration to regions with lower average temperatures is another means of adaptation. This is a potentially limited option, however, as the costs of changing one's place of residence are substantial for those contemplating it, and borders between states pose formidable political, cultural and administrative constraints. Migratory movements linked to global warming are more likely to occur within the same country. For wealthy countries, for example, from metropolises to the coast or mountains, or for poor countries from rural areas to capital cities.

It is no longer acceptable to ignore all the earthlings whose lives will be shortened when we have increasingly complete and reliable data on mortality linked to rising temperatures. Counting the missing people if we fail to act on climate change brings us face to face with our responsibilities, and justifies ambitious investments in mitigation and adaptation.

Before returning to Sirius, Micromégas left a book for the inhabitants of Earth. It should enable them to see "the end of things". When men open it, they discover blank pages. Voltaire would remind us that "Man is not made to know the intimate nature of things, that he can only calculate, measure, weigh [...]". That's not so bad!

François Lévêque, Professor of Economics, Mines Paris

This article is republished from The Conversation under Creative Commons license. Read the original article.